MM & GY & TY v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2015] EWHC 3513 (Admin) (03 December 2015)

MM & GY & TY v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2015] EWHC 3513 (Admin) (03 December 2015)

This damaging decision for the British government was published immediately after David Cameron slanderously accused those opposed to expanding UK airstrikes against “Islamic State” of being a “bunch of terrorist sympathisers”. Overall the crude ultimatum probably deterred MPs from defying Cameron. To compliment existing British military strategy in Iraq, they voted 397 votes to 223 to approve airstrikes against ISIS in Syria; a move that made bombing jihadi militants in Raqqa – the “head of the snake” which must be crushed – a reality. But in this robust judgment handed down the very next day, Ouseley J defiantly quashed three decisions by the home secretary to refuse British citizenship to the wife and two adult children of a former member of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ); a bloodthirsty preacher named Hany el Sayed el Sabaei Youssef (HY) who glorifies slain terror mastermind and former al-Qaida boss Osama bin Laden. Although HY’s wife and two adult children did satisfy statutory requirements for naturalisation, Theresa May exercised discretionary power to refuse them naturalisation in order to deter potential extremists from manifesting fundamentalism by sending out a clear message that their family members would not be naturalised as a consequence of their activities.

However, it was argued that MM, GY & TY are “blameless individuals whose character is unimpeachable” who had been punished “for the sins of their father”. The court agreed and chastised the home secretary for not grappling with the issues created by her policy and held that her stance was irrational because her position lacked internal logic. On the one hand, Ouseley J was invited to rule that executive action of this nature is inimical to democracy and the rule of law. On the other hand, arguments were aired that citizenship is a privilege – and not a right – which can be rationally denied to spouses and blood relatives of extremists. However, the home secretary’s attempt to disincentivise extremism backfired and the court held that it is unfair to refuse naturalisation with a view to providing a general deterrent to others. This post takes a look at this case and also provides me a chance to vent frustration at world affairs.

Overview

In a judicial review application arising out of the following facts, Ouseley J found prima facie “real unfairness” where naturalisation was refused to someone who qualifies in all other respects, so as to provide a general deterrent to others, over whom the applicant has no control. On 21 May 2009, MM, GY and TY were granted indefinite leave to remain (ILR). Holding Egyptian nationality, they applied for naturalisation in September 2011, August 2012 and August 2011 respectively and their applications were refused along similar lines in August 2014. The refusals were justified on the basis of deterring potential extremists from involvement in extremist activities and stressed that any extremist activity could affect the immigration and nationality status of close members. GY and TY are married and employed. EY’s daughter is a teacher, has two children and is married to a British citizen. His wife is in poor health and is bedridden.

Originating in Egypt in the 1970s, EIJ is a terrorist organisation and wants to create an Islamic state in Egypt by violent means. It began to flourish during the Afghan jihad against the Soviets and Ayman al-Zawahiri became its leader in 1991. Although HY is not considered a current threat to UK national security, Theresa May does rightly assess him as an Islamic extremist but she took things too far by trying to punish his family because of him and his violent views.

The United Nations Sanctions Committee put HY on the terrorism sanctions list pursuant to UN Security Council Resolution 1617 (2005) for being associated with al-Qaida through EIJ: a very interesting pair of 2010 UK Supreme Court judgments involving HY can be read here and here. The UK believes that he still holds extremist views but is unlikely to participate in terrorist activities and efforts to have him removed from the list have been unsuccessful. He was granted exceptional leave to remain (ELR) subsequent to being refused asylum because his deportation to Egypt would result in ill-treatment contrary to article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).

HY, who lives off the public purse, is a condemnable individual and recently told an interviewer on Lebanese television: “It’s beneath me to be interviewed by you. You are a woman.” Even more chillingly, HY is said to have mentored the terminated ISIS executioner Jihadi John and it has also been reported that he was one of the “key influencers” of the lunatics guiding/supervising the actions of the Sousse gunman Seifeddine Rezgui. We clearly live in extremely touchy times and even Guantánamo returnee Shaker Aamer, who was held captive without charge for nearly 14 years for being bin Ladin’s right-hand man and alleges that British authorities were complicit in bringing about his predicament, has expressed solidarity with the government by telling jihadis and their sympathisers to “get the hell out” of the UK. However, Aamer nevertheless thinks that Abu Qatada is not a “bad guy”. It will be interesting to see whether the Saudi will take British citizenship and whether Theresa May will grant it to him without resorting to the type of behaviour evidenced in the instant case.

It was decided in late 2012 that HY was guilty of acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations and was excluded from refugee status under article 1F(c) of the Refugee Convention 1951 on the basis of his membership of a proscribed organisation. He won his appeal at first instance but lost thereafter and his case is being re-determined. His continuing involvement in EIJ and support and glorification of terrorism fuelled his exclusion; for e.g. the UN Security Council Committee pursuant to Resolution 1267 (1999) – or the al-Qaida Committee – found that he publicly praised al-Qaida and encouraged others to revere it as well. The home secretary’s counsel confirmed that the refusal was not reflective of some lurking doubt about the claimants’ good character and she did not have “an unexpressed but lurking doubt about the character or views of the applicants.” The relevant part of section 6(1) of the British Nationality Act 1981 (BNA) states:

If, on an application for naturalisation as a British citizen made by a person of full age and capacity, the Secretary of State is satisfied that the applicant fulfils the requirements of Schedule 1 for naturalisation as such a citizen under this subsection, he may, if he thinks fit, grant to him a certificate of naturalisation as such a citizen.

As far as the home secretary could see, no specified constraints restricted the exercise of discretion because it turned on the state’s relationship with the individual. From that angle, she suffered from the misconception that her discretion was wide enough to accommodate public policy considerations of the nature invoked in the present case. Comparisons were also drawn with deterrent sentencing in criminal cases and criminal deportations in light of which blameless families might suffer because of the activities of a criminal family member. Yet none of the arguments advanced by the home office convinced the court and it found against the government on virtually every point.

Arguments

On the claimants’ view, the discretionary refusal power is only exercisable where its use relates to the suitability of the individual for naturalisation. Both the section 6 provision and the instructions focus on the attributes of the individual adult applicant, including his individual character, good or otherwise. Grants and refusals focus on the individual and Parliament did not intend for discretion to be used to refuse naturalisation to an applicant who meets the statutory tests and was not an extremist. An applicant’s family member’s extremist views, or those of another unconnected person or the fact that an applicant had not broken off relations with an extremist family member played no part in the equation.

In view of what was at stake for the individual, the discretionary power needed to be exercised reasonably, proportionately and fairly. The family unit, society’s natural and fundamental building block, is entitled to the state’s protection and the importance of the family bond had been recognised in K v SSHD [2006] UKHL 46. To require an applicant who satisfied the good character test to sever family relations with an extremist equates to making the destruction of family life the price of British nationality and simply using someone’s family as a ground to take action them is arbitrary.

The claimants did not partake in the misconduct invoked against them; it was not their doing, they could not have been aware that it could impact their applications, its scope was wider than HY’s acts and the point had not been made that they needed to do more to stop it. Refusing citizenship, an important status, was damaging – especially for those with roots who consider the UK their home – and caused important benefits from being conferred. As the Supreme Court held earlier this year in the case of Pham v SSHD [2015] UKSC 19 – a case about deprivation of citizenship/terrorism, a suitably intense standard of judicial review is required in respect of discretionary refusal decisions. The standard must be based on necessity, appropriateness, suitability and the balance of advantages and disadvantages, including but going beyond whether the decision was arbitrary or conspicuously unfair: see my analysis of Pham on the UKSC Blog and SSRN.

It was also said that the interference caused to article 8 of the ECHR (and also articles 8 and 14) by requiring an applicant to renounce family connections so as to advance and succeed in an application for naturalisation would not only be arbitrary but would also amount to unjustified discrimination on the basis of family ties. As in Genovese v Malta (2014) 58 EHRR 25, ECHR rights would be in breach. An approach such as this could not prevail in naturalisation decisions because the aim was illegitimate, the means were disproportionate and no connection existed between what the applicant had done or could do and the family member’s extremist tendencies.

In addition to drawing parallels with deterrent sentencing in criminal cases and criminal deportations, the home secretary responded by running her arguments as follows. She said that the fulfilment of the statutory tests to her satisfaction was the gateway to a species of limitless and unrestricted discretion, which was not confined to the applicant’s suitability for naturalisation. The home secretary’s actions had been aimed at deterring extremism. Thus, to set an example by not naturalising family members remained relevant to and had been legitimately considered in the exercise of the statutory discretion which was broad enough to include public policy considerations such as those thrown up in this case. Full age, capacity and the focus on the applicant’s character did not render associations irrelevant. In official eyes, the non-arbitrary fact-specific decision was not made under a blanket policy, it was justified and legitimately aimed to deter others from behaving like HY and it was submitted that no heightened standard of review exists for naturalisation decisions. Naturalisation was not a right but a privilege.

The claimants’ reliance on post-decision Nationality Instructions issued in March 2015 to put a gloss on things did not help them. No interference with article 8 was made out because the applicants and HY’s family life before and after the applications remained the same and no interference was discernable. Article 14 was not even engaged. Equally, as held in Al-Jedda v SSHD [2013] UKSC 62 and Genovese, article 8’s interaction with naturalisation decisions was limited to cases of arbitrary denial of citizenship.

Decision

Ouseley J held that a very broad discretion was required to be able use naturalisation decisions to modify the behaviour of others. To his Lordship’s mind, Parliament would have provided for such a broad discretion expressly if it had intended to confer such a power on the home secretary. Therefore, the home secretary has no discretion to refuse citizenship by naturalisation under section 6(1) of the BNA with a retaliatory view to deter potential extremism by sending out a message that extremists’ family members would not be naturalised in consequence.

It was obvious that none of the claimants failed the good character requirement and none of the adverse factors (e.g. crime, deception, tax evasion, terrorism) listed in the Nationality Policy Guidance Casework Instructions, chapter 18A, annex (d) version 2013, were present in their cases for them to be refused naturalisation. However, in doubtful cases the instructions allowed the decision-maker some leeway to refuse the application nevertheless. Under the guidance, “good character” requires the applicant to have observed the laws of the UK, shown respect for its rights and freedoms and have fulfilled his or her duties and obligations as a resident. Noting that good character is classifiable as conceptually “nebulous”, in R (Al–Fayed) v SSHD (No 2) [2000] EWCA Civ 523 Nourse LJ held at para 41 that a high standard applies in the home secretary’s evaluation whether she is satisfied that a person is of good character and so long as she behaves reasonably the courts should not discourage her from employing a high standard.

Naturalisation would have been refused on good character grounds if the claimants shared HY’s alleged extreme views. Yet the purported reasoning was unambiguous that, by using pre-emptive/coercive techniques, the refusal intended to act as a tool to deter potential extremism from being manifested because of the negative consequences refusal of naturalisation would produce for alleged extremists’ close family members – who, of course, were themselves of good character. For the approach to make sense within its own terms, it needed to be applied quite generally.

Importantly, Ouseley J discerned at para 28 that the expression “potential extremists” was telling because it did not interlock with HY’s behaviour despite purporting to do so. He was an extremist of “of long-standing and firm convictions” and the rationale underlying the refusals was clearly targeted at potential extremists. Therefore any deterrence was not aimed at HY who is clearly a man with some serious history to have been listed by the UN for his public praise and glorification for al-Qaida. In the event that his Lordship was incorrect and the exercise of discretion was to deter actual extremists from extremist activity, HY would still fall outside the target area/sweet spot as the home secretary accepted that despite his monstrous views he no longer engages in extremist activities. Ultimately, the aim is to deter radical Islamists from acting on their extremist views (including coaxing others to embrace them) rather than dissuading them holding extreme views. The court’s analysis of the aim of the exercise of discretion was that no connection between the applicant for naturalisation and such a potential extremist was necessary and instead:

28. … It is merely necessary, for the intended deterrent effect to arise, that the potential extremist should know that the home secretary will exercise the discretion against the grant of naturalisation to his or her own family members albeit of good character.

Ouseley J also found the scope and purpose of the statutory discretionary power, as exercised in this case, to be “unclear” and at para 29 the court said that the parties “found difficulty” in pinpointing the extent of the power’s coverage. The government argued that the discretion could be relied upon to support general refusals of a particular nationality or invoked in aid of a general moratorium on the grant of naturalisation. The court rejected the claimants’ suggestion that persons who are outwardly acceptable but have associations leading to doubts about their loyalty or security risk fall to be dealt with as a matter of discretion. In light of the Nationality Instructions’ guidance on associations, Ouseley J observed that this point is a component of good character and he held:

29. … The statutory discretion is not to be exercised on what are essentially good character grounds simply because the evidence on good character does not support refusal on that ground. The good character test is broadly expressed, and the home secretary has ample scope for a broad judgment under it as to whether the evidence satisfies her or not. And doubts about character can be resolved adversely to the applicant.

Clearly, the tests in the BNA and the accompanying instructions focus on the individual’s merits for naturalisation. Because of the BNA’s focus on an individual’s application and in view of the home secretary’s very broad express power to prescribe requirements for measuring an applicant’s good character and to refuse naturalisation when unsatisfied of such character, the court held at para 31 that that Parliament had not conferred the discretionary power on the executive for the pursuit of broad and general public policy objectives. The discretion was not residual. Instead, the discretionary power was there as a “backstop” to cover the possibility of “the unforeseen eventuality”.

In this case, the factor leading to the exercise of discretion was unrelated to the applicants’ personal or individual qualities, attributes or failings and the deterrent possibility arose as a consequence of their relationship to HY whereas the decision’s underlying deterrent purpose purported to target persons other than them. The factor applies irrespective of whether an applicant has any ability to control what those others may do or think and regardless of whether any connection exists between the individual applicant and any person at whom the deterrent seeks to target.

Using naturalisation decisions to influence the behaviour of persons unconnected to the applicant would require Parliament to confer a broad discretion and so the existing limited backstop discretion was not a substitute for the broad discretion required to cover the home secretary’s behaviour. The broad discretion contemplated would allow otherwise successful applications to be refused for reasons in the service of some general public interest, as judged by the home secretary. Ouseley J explained at para 32 that on the home secretary’s case, the contended power potentially covered all criminal or undesirable activity and his Lordship held: “Such a purpose does not come within the scope of a limited backstop discretion.”

Irrespective of whether the discretionary power was broad or backstop, the court in any event found:

33. … real unfairness, on the face of it, in refusing naturalisation to someone who qualifies in all other respects, in order to provide a general deterrent to others, over whom the applicant has no control.

Observing at para 35 that the point was not “new”, Ouseley J accepted that (a) the executive was entitled to examine the discretionary tools in her armoury to deter and prevent extremist activity and (b) the fact that its exercise on this basis was unprecedented did not make it unlawful. Yet he held at para 34 held that by exercising the discretionary power in the manner that she did, Theresa May was using it beyond its statutory scope and purpose for some other more general societal purpose than the one conferred by the BNA. His Lordship reasoned that although the spectre of Islamic extremism was relatively new, it was open to Parliament in 1981 to consider the issue as regards whether deterring criminals or other undesirable aliens from their activities should be achieved by the prospect of their otherwise suitable family members being refused. In the court’s final analysis:

35. … Yet Parliament has not provided for this expressly in the BNA, as in my judgment it would have done had so unusual a use of a discretionary power related to an individual’s circumstances been intended.

Moreover, at para 36, the court rejected the parallels drawn by the home secretary between the use of discretionary power in the present case and (a) the effect on the family of a criminal of passing a deterrent sentence, or (b) the effect on a criminal’s innocent family of deporting them along with the criminal. In both examples, the innocent family suffered because of the need to punish or remove the criminal. On proper analysis, that was the opposite of what the home secretary sought to do. Satisfied that the exercise of the discretionary power was unlawful, Ouseley J therefore held:

36. … The true parallel would be the punishment of the family of one criminal to deter the criminals in other families. That is a power which would no doubt find its supporters, but is not one which Parliament should be taken to have conferred in relation to naturalisation by the grant of this discretion in this Act.

Comment

Somewhat ironically, Ouseley J’s delivery of this judgment, which symbolises a serious blow to the home secretary’s anti-terror campaign, coincided with revelations that the Belgian-Moroccan jihadi Abdelhamid Abaoud – the 28-year old mastermind of last month’s terrorist attacks in Paris – used to come and go from the UK as he pleased despite the fact that the UK terror threat was set as “severe” (falling just a notch short of the “critical” level). He apparently had photographs of potential targets in Birmingham on his mobile phone.

With terror attacks spiralling out of control, Islamophobia is also rising at an astronomical rate. And despite the prime minister’s attack on people opposing air raids against ISIS in Syria, his government is clearly seen as weak and compromised by Donald Trump who wants a blanket ban on Muslims entering the US. Cameron said Trump’s comments were “divisive, unhelpful and quite simply wrong.” The chancellor George Osborne opined that the tycoon was talking “nonsense” and Boris Johnson declared Trump “unfit” to enter the White House. Interestingly, if we draw parallels, Trump’s views on women seem to converge with those held by HY. Unsurprisingly, the Supreme Court also dumped Trump today by unanimously dismissing his appeal in Trump International Golf Club Scotland Ltd & Anor v The Scottish Ministers (Scotland) [2015] UKSC 74, a case in which he tried to bully Scottish ministers in relation to their approval of plans for a renewable energy development within sight of his golf development which opened at Menie in July 2012.

Nobel peace prize winner and human rights activist Malala Yousafzai said Trump’s comments were “tragic and full of hatred” and would only “radicalise more terrorists”. Moreover, as Charles Moore wrote last Friday, if Trump had substituted “Christians”, “Hindus” or “Jews” for “Muslims” in his vitriol it would be the end of his political life. Loads of republican voters back Trump despite him being dubbed “lizard brain” by his republican rival Dr Ben Carson, who is quite an offensive character himself. Yet Trump, who is now almost universally known as a “nasty” individual, claims to be “least racist person on Earth”; he denies historic accusations about not renting property to black tenants and claims that he “will bring peace and unity” to the world if elected US president. To his credit, Trump does have the dubious accolade of being held in high esteem by the tyrannical Vladimir Putin who chose to describe the republican hopeful for the White House as “flamboyant” and “very talented”.

I’m only mentioning Trump as one of his supporters has already given me a taste of the type of racism that is brewing in the UK. The day Trump made his remarks, which startled even the likes of Marine Le Pen, totally out of the blue a man randomly told me in a London supermarket that everyone disagreeing with the billionaire was “in the five per cent.” Nothing in my acts or appearance gives me away as Muslim so I’d expect that British Muslims, who generally resist western influences by relying on Islam as a shield, will be hit quite hard by the tide of fear based illiberal white supremacy presently fashionable in Europe and America. For my part, in order to “deconflict” things in everyday life I don’t even mind “converting” to Christianity, Hinduism or Judaism to assimilate/integrate in the host society but I doubt very much that others will feel inclined to do the same.

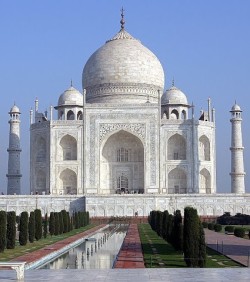

Trump is not America, but who knows he could become president. And if he does, then Cameron’s pride in the UK’s Muslims will be varpourised (like Jihadi John was by a Hellfire missile) and he will embrace the property mogul as he recently did the Hindu fundamentalist prime minister of India, the one and only hatemongering extremist Narendra Modi who reveres Gandhi’s murderer is now even claiming that the Taj Mahal is a Hindu monument. If anything, Modi’s India only proves that despite upheaval, refugees and mass killings, Partition was the best solution for India and Muslims who left India made a superior choice irrespective of the horrors presently besetting them in Pakistan.

Trump is not America, but who knows he could become president. And if he does, then Cameron’s pride in the UK’s Muslims will be varpourised (like Jihadi John was by a Hellfire missile) and he will embrace the property mogul as he recently did the Hindu fundamentalist prime minister of India, the one and only hatemongering extremist Narendra Modi who reveres Gandhi’s murderer is now even claiming that the Taj Mahal is a Hindu monument. If anything, Modi’s India only proves that despite upheaval, refugees and mass killings, Partition was the best solution for India and Muslims who left India made a superior choice irrespective of the horrors presently besetting them in Pakistan.

For example, Delhi’s chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, condemned Modi in a tweet yesterday calling him a “coward and a psychopath” for using strong arm tactics by conducting an unwarranted anti-corruption raid on his office. Kejriwal’s Aam Aadmi party (literally “Common Man party”) called the actions “a witch-hunt” and its spokesperson Raghav Chadda lambasted Modi for “following the footsteps of Adolf Hitler”. Equally, Sonia and Rahul Gandhi of the Congress party have also accused Modi of engaging in a “political vendetta” against them. “India is being ruled by a Hindu Taliban” and “Narendra Modi is clamping down on tolerance and freedom of expression,” wrote Anish Kapoor last month as the Indian premier visited London. But, or course, all this does not stop Modi from being given “rock-star” receptions by western leaders such as Obama and Cameron.

Even though Trump has wrecked his own brand and is automatically being punished for his comments by the global business community, it a cruel paradox that a woman such as Maryam Rajavi can be excluded from the UK so that deals can be done with Tehran’s hardline Ayatollahs and Trump – who continues to taunt the UK about its Muslim “problem” by pointing out that more British Muslims have joined ISIS than the armed forces – can provoke communal tensions in an inflamed environment and is allowed to walk away unscathed despite his exclusion being demanded by the public. By contrast, Rajavi is excluded despite being invited to the UK by parliamentarians who want her to address them on democracy in Iran.

Speaking of deals, Boris Johnson, well-known for his extreme sense of humour, is twisting the political knife in David Cameron’s back and the London mayor has openly attacked Number 10’s strategy in the Syrian war. Johnson is advocating a deal with the Devil; he says that the UK should partner with Assad to wipe ISIS out. If that is the case then the UK has made a U-turn on Syria by surrendering its long-held “Assad first” strategy, which in any event seems doomed given that Syria’s third largest city Homs – the heart of the revolution – has been handed over to the Damascus regime in a ceasefire deal backed by the UN.

It seems that the dictator is now on the verge of becoming the west’s ally against ISIS, a strategy which is plainly at odds with ground realities. If that is so then the UK is headed for an alliance with a mass-murdering regime responsible for most of the 300,000 civilian fatalities in the conflict. The authors of ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror argue that Assad is responsible for buttressing ISIS and may not be a reliable ally in fighting the group. The dictator is said to have emptied Sednaya prison (outside Damascus) of the most dangerous Islamists and apparently also released three top ISIS commanders in a strategic move. As shown by Nadir Syed’s trial, an extremist individual wanting to conduct the first UK beheading, Assad’s strategy is not dissimilar to the British authorities’ tactic of allowing dangerous people to exit the UK rather than dealing with them here. Moreover, accusations have also been made about Damascus (and not Ankara) being the biggest beneficiary of oil related activity and trade with the jihadis.

Perhaps the “terrorist sympathisers” aren’t so stupid after all.

Reblogged this on Refugee Archives @ UEL.