A catchall by design paragraph 322(1A) of the immigration rules has required clarification from the courts time and time again. The approach adopted by the Court of Appeal in this case contrasts quite starkly with the harsh decision of the Upper Tribunal in FW (Paragraph 322: untruthful answer) Kenya [2010] UKUT 165 (IAC) which has been analysed here.

In the present case the Court of Appeal took a different approach to the one adopted by the Upper Tribunal in FW’s case.

Rule 322(1A) requires that leave to remain in the UK should be refused:

“where false representations have been made or false documents or information have been submitted (whether or not material to the application, and whether or not to the applicant’s knowledge), or material facts have not been disclosed, in relation to the application.”

The word “deception” is not used in paragraph 322(1A). Instead it is defined, for the purposes of paragraphs 320(7B) and 320(11), in paragraph 6 of the immigration rules, as “making false representations or submitting false documents (whether or not material to the application), or failing to disclose material facts”.

The facts

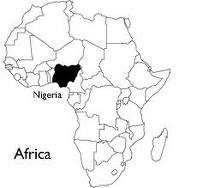

In the present case Mr A was a Nigerian national who had obtained a first class BSc (Honours) degree in the UK. Thereafter, he successfully completed an MSc degree. However, during his time in the UK he fell foul of the criminal law because of being caught by the police for driving without insurance and a valid driving licence on three separate occasions (twice in 2004 and once in 2006). Oddly the Police National Computer contained only one entry for these three offences and in his leave to remain was extended in 2007 until 31 January 2009. The application considered by the Court of Appeal (Rix, Longmore, and Jacob LJJ) related to an extension under the PSW scheme. In his evidence in the then Asylum and Immigration Tribunal, Mr A accepted his criminal antecedents but when he applied under the Tier 1 (Post Study Work) (“PSW”) route he had not disclosed this information on his application form.

The PSW application invited Mr A to answer the following question:

“E1. Has the applicant had any criminal convictions in the United Kingdom or any other country (including traffic offences) or any civil judgments made against them?”

The question on the PSW application was qualified by the following dispensation in the UK’s criminal law under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 (“ROA”) which allows persons with criminal convictions to withhold disclosing these:

“Note 1 – Convictions spent under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act need not be disclosed. More information about the Act is given toward the end of the section.”

Notwithstanding the inapplicability of the ROA to his case, Mr A, who believed that his convictions had been “spent”, answered question E1 set out above in the negative. Concomitantly, bearing Mr A’s criminal antecedents in mind, the Secretary of State for the Home Department (“SSHD”) refused Mr A’s application by relying upon Rule 322(1A).

In his refusal letter the SSHD explained to Mr A that the terms of rule 322(1A) are such that upon its engagement rule 320(7B) is automatically engaged, save where an applicant’s rights are breached under the Human Rights Act 1998 or the Refugee Convention 1951, with the effect that from the date of the relevant immigration decision an applicant’s future applications are to be automatically refused for a period of one to ten years depending upon when and how (i.e. removed forcibly or otherwise) the applicant chose to depart from the UK.

The meaning of the word “false”

The word false has many meanings in English. The Court considered it “a remarkable feature of a language as rich as English” that the word false has two meanings. Firstly, false means “wrong” or “incorrect” but alternatively it also means “lying, deceitful, treacherous, unfaithful to; deceptive; spurious, sham, artificial” and the like. The Court observed that while the civil law focused on misrepresentation which can be innocent, negligent, or fraudulent, under the criminal law to establish mens rea (“something more than mere inaccuracy”) was required.

Rix LJ, for whom false meant lying or being deceitful, cited Staughton LJ in Tahzeem Akhtar v. Immigration Appeal Tribunal [1991] Imm AR 326 at 332/3 who took the view that the word false took the first meaning, namely that:

“… false representation is one that is inaccurate or not in accordance with the facts. I say that, first, from the ordinary use of the English language and, secondly, because it seems to me that that interpretation squares more easily with the words in the rule “whether or not to the holder’s knowledge”. I agree that there is an alternative explanation for those words being in the rule, that is to say, to cover the case when somebody else has made a fraudulent representation. But to my mind they were inserted to show that representations, either by the holder or by anybody else, need not have been fraudulent…”

The debate

On 17 March 2008 when the changes to the immigration rules (HC 321), which introduced paragraphs 320(7A), 320(7B) and 322(1A), were debated in the House of Lords, Lord Avebury argued in favour of disapproving them. He said because of the strict terms of paragraph 322(1A) there was every possibility that a clerical error such as the submission of the wrong document would mandate a refusal “even where there was no intention to deceive”. Baroness Warwick of Undercliffe raised concerns about the consequences of paragraph 320(7B) for students and how they could be banned for a period of ten years from re-entering the UK by reason of a previous false statement. For her it was “not clear from the rules as formulated whether ‘false’ has the meaning of mere inaccuracy, which is one ordinary dictionary meaning, or whether a deliberate fraud must be attempted.” Moreover, Baroness Hanham expressed concern about children who might have their applications refused because of false representations made by adults or parents who had assisted them.

In responding to these issues, on behalf of the government, Lord Bassam made a “concession” by saying that persons who left the UK before 1 October 2008 willingly would face no liability under rule 320(7B). Lord Bassam did not provide any assurances about the meaning of the expression “false representations” but he did explain that a “false document” is a “document that is forged or has been altered to give false information…[i]t will be for the BIA [the Border and Immigration Agency as it then was – now the UKBA] to prove that a document is false, and the standard of proof has to be very high”

ILPA and the minister

On 26 March 2008 the Immigration Law Practitioners’ Association had written to the then Minister for Immigration Liam Byrne MP to clarify the effect of the changes introduced by HC321. The letter stated:

“Falsity

We are pleased to have clarification that the reference to falsity in paragraph 33 of HC 321 implies an element of deliberate falsehood and not a mere mistake. Written confirmation that the comments apply as much to statements as to documents may be belt and braces, but would be appreciated nonetheless.”

In response to ILPA’s letter the Minister wrote back stating that:

“You go on to ask for confirmation that Lord Bassam’s comments about the definition of a false document also apply to false representations. We have published guidance to Entry Clearance Officers, in Chapter 26 of the Entry Clearance Guidelines, which I believe deals with this point. The new Rules are intended to cover people who tell lies – either on their own behalf or that of someone else – in an application to the UK Borders Agency. They are not intended to catch those who make innocent mistakes in their applications.”

At paragraph 42 the Court examined the contents of Chapter 26 of the Entry Clearance Guidelines to conclude that the word “false” used in the context of this guidance was in relation to the secondary meaning of the word, i.e. when the word takes the connotation of “lying” or “deceitful” behaviour than the plain meaning of the word which denotes incorrectness.

Mr A’s submissions

Mr Zane Malik made the submission on behalf Mr A to the Court of Appeal that whatever the rule by itself may have meant, Lord Bassam’s assurances and the letter combined require the rule to be “read down” and therefore the rule can only apply only to dishonestly made false representations. Mr Zane Malik further expanded the thrust of his arguments so as to amend the rule, i.e. the Secretary of State’s policy, to the same effect. It was further submitted that there is/was an element of discretion into the decision which should therefore take account of the applicant’s state of mind. Having sought a redetermination Mr Zane Malik also submitted that it was necessary to come to a view as to Mr A’s honesty, and that can only be done by the AIT (now FTT(IAC)) as it is the tribunal of fact.

Conclusion

The Court unanimously decided that, notwithstanding what Staughton LJ said in Akhtar, there was an open choice in the relevant rule in relation to the meaning of the word “false” and that the Court preferred to associate the word with “dishonesty” (see especially Rix LJ at [65] and [66]). The court enumerated eight reasons why it formulated this view and these are set out in the judgment at [67]-[75].

Ultimately the Court of Appeal agreed with Mr Malik’s submissions and remitted the case to the tribunal for a redetermination. Longmore LJ (at [87]) expressed his concerns by stating that he was “perplexed” by the fact that the correct state and meaning of the immigration rules could only be understood after a trawl through Hansard, correspondence between ILPA and the Minister for Immigration, the very complex rules themselves, and the plethora of other guidance documents which can be found on the UKBA website.

Ultimately the Court of Appeal agreed with Mr Malik’s submissions and remitted the case to the tribunal for a redetermination. Longmore LJ (at [87]) expressed his concerns by stating that he was “perplexed” by the fact that the correct state and meaning of the immigration rules could only be understood after a trawl through Hansard, correspondence between ILPA and the Minister for Immigration, the very complex rules themselves, and the plethora of other guidance documents which can be found on the UKBA website.

As stated earlier this case contrasts very starkly with FW (Paragraph 322: untruthful answer) Kenya [2010] UKUT 165 (IAC) not only because of the factual similarity but also for the reason that both cases involved PSW visas and involved paragraph 322(1A) and related rules. It is unlikely that this judgment will sit well with the Secretary of State for the Home Department.